This week it's a kitchen sink beer from our old friends Barclay Perkins. I picked out this beer because of its weird and wonderful list of ingredients. There was a war on, you know.

KK was part of the standard range of draught beers of London breweries. It was usually the strongest draught beer you'd find in a pub. Its origins can be fiound in the 19th century when breweries had two sets of Ales: mild X Ales and Stock (or Keeping) K Ales. Dark and quite well-hopped, it doesn't fit well with modern style calassifications.

In the public bar, KK would have been called "Burton". In the 1930's it sold for 8d a pint and had a gravity of around 1055. Burton was still a standard option in London pubs well past WW II. It gradually petered out in the 1960's. In the 1970's Fuller's dropped their Burton and replaced it with ESB. Currently, the only survivor of the style is Young's Winter Warmer, which had its name changed, presumably when the monicker Burton became a liability.

Now here's Kristen tio guide you further . . .

Barley Perkins 1942 KKDrum roll....for the first beer in the anything alcoholic month of June is....BP's 1942 KK (one K shy of being evil). This beer is the epitome of being ANYTHING alcoholic. It has pretty much everything you could possible throw into a beer. Is it a mild? Hmm...maybe? This is definitely not really like anything else we've ever done on this thing.

Brewing liquorThis is one of the most tanted brewing liquors I have seen. 6 different brewing salts are added to create the 'KK' brewing water. Lots of gypsum and epsom salts. If you want to make it more 'traditional' I would suggest the following for a start:

Gyp - 3g/ gal (4L)

Ep - 2g/ gal (4L)

Chalk - 0.5g/ gal (4L)

GristIts definitely not as big as older versions of the KK but its got a good amount of crystal and sugars in it. These aren't the dark sugars as most of the color comes from the dark caramel colorant. The two pale malts are actually mild malts. Its hard enough finding one mild malt

so substituting any good quality pale malts would work just fine. Nearly 5% of this sucker is rye malt which is higher than I've seen in any other beer. Speaking of which, there are nearly 25% adjunct ingredients!

HopsThe hops are relatively fresh and suprisingly quite high. With around 40bu of bitterness this beer would pack a pretty good punch ESPECIALLY with the lower gravity.

Tasting notes

Tasting notesGraham crackers, Scottish biscuits and a touch of dark fruity figs. Lots of hay in the nose with hints of minerals. Lots of spicy hops and rye in the flavor. Some light sultanas and toast from the amber malt. The bitterness comes through quickly and brightens up the finish. The mineral character really drys out the end and extends the flavor for quite a while.

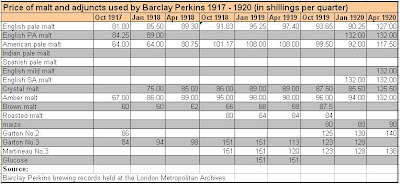

"I discovered something really fascinating about the relative prices of malt, sugar and maize in WW I today, Dolores. . . . Dolores . . . Dolores!"

"I discovered something really fascinating about the relative prices of malt, sugar and maize in WW I today, Dolores. . . . Dolores . . . Dolores!"