Today there's more from "Brewing Science & Practice" by H. Lloyd Hind, published in 1940. Sparging. What a great word. I wonder what its etymology is? Zythophile will probably know.

Today there's more from "Brewing Science & Practice" by H. Lloyd Hind, published in 1940. Sparging. What a great word. I wonder what its etymology is? Zythophile will probably know.Sparging

The object of sparging was to wash out as much of the remaining extract as possible after the wort had been run off at the end of mashing. Care had to be taken not to extract substances contained in the grains which might have a negative effect on the clarity or stability of the finished beer.

The water used for sparging was usually 168 to 170º F. Sometimes the process began with water at a slightly cooler temperature, 167ºF, which was gradually raised to 170ºF. It was important that the sparge water was distributed evenly over the surface of the mash and that it was able to percolate through all of it. If channels formed in the mash, not all the grains would be properly washed by the sparge water. The amount of sparge water used was restricted so that the total quantity used for mashing and sparging was no more than 6.5 or 7 barrels per quarter of malt.

Often the taps were opened as sparging began. The wort was run off at the same rate as sparge water was added. This kept the level or wort in the mash constant and prevented suction which might draw sediment into the wort.

Sparging ceased when the gravity of the wort running off had fallen to 1002-1003º. Wort at lower gravities was of little value and could cause problems with clarity and stability. In some breweries such very dilute worts were used as "returns", that is in place of water in a subsequent brewing.

Sparging ceased when the gravity of the wort running off had fallen to 1002-1003º. Wort at lower gravities was of little value and could cause problems with clarity and stability. In some breweries such very dilute worts were used as "returns", that is in place of water in a subsequent brewing.A "dead mash occurred" when the grains had become so compacted that the wort would not run off. The reason for a "dead mash" could be:

1. standing too long

2. running off the wort too quickly

3. sparging too fast

4. "steely" (hard) malt

5. too deep a mash tun

A dead mash could be loosened by rotating the mashing rakes a couple of times or by a quick, strong underlet.

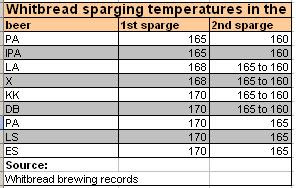

Whitbread and Barclay Perkins both sparged twice, once after each underlet. The second sparge was usually at a lower temperature than the first. Both breweries sparged at a wider range of temperatures than those indicated by Hind, varying from a low of 155º F to a high of 174º F.

Whitbread had basically 4 sparging regimes:

- Pale Ales (IPA, PA)

- Milds (LA, X)

- Strong Ales (DB, KK)

- Porter and Stout (P, LS, ES)

Barclay Perkins practice was somewhat different. The first sparge was almost always at 170º F, except in the case of the Strong Ale KKKK and BBS Stout. Unlike Whitbread, the second sparge was coldest for Pale Ales (PA, IPA) than for Milds (XX, X, A). Most of the Porters and Stouts (TT, BS, OMS) had no sparge after the first underlet. IBS Export, Russian Stout, had a mashing scheme different to all the other beers, inclusing a very cool second sparge.

5 comments:

It I'm reading my OED correctly, the verb "to sparge" in the brewing sense entered the lexicon in the early nineteenth century. The noun "sparge" (meaning "the action of sparging"), appears at the same time.

Both stem from the earlier verb "to sparge" (also "sparget"), meaning "to sprinkle," probably influenced by Old French "espargier" ("to sprinkle"), and Latin "spargere," meaning the same. With this sense, "sparge" entered English in the late sixteenth century.

According to the OED, the earliest use of the word "sparge" is in late Middle English, meaning a form of rough-cast plaster. Which would have been, I'd guess, sprinkled.

I seem to remember reading something once about Guinness experimenting with using the lowest-gravity sparge runoff as water to be boiled in the brewery's steam engine...

FYI - dead mash is also called a 'stuck' mash. Basically its when the grain bed is compacted so nothing can run through.

What is the difference I wonder between a single mashing and a thorough sparge and successive mashes (1800's parti-gyle style) where the worts are all (100%) mingled? Is the extract the same in each case? Is the only differnce one of timing of the various steps...?

Gary

Gary, conveniently, brewing logs always give the extract, measured in brewers' pounds per quarter (approx 336 pounds) of malt. I've not seen a big difference.

Here's an example: Barclay Perkins Porter 1848 with two mashes and a sparge, 88.7 brewers' pounds per quarter. The 1936 version with mash, underlet, 2nd underlet and sparge: 86 brewers' pounds per quarter.

Except in wartime. I can't recall seeing just a single mash and one sparge. The classic 20th century way of mashing was mash, underlet, sparge, underlet, sparge.

If anything, they went more crazily in search of extract in the 19th century. They were getting 85-90 pounds of extract per quarter and a return wort. In the 20th century, they didn't bother do much squeezing that last bit of extract out of the malt.

Post a Comment