alexei wants to play the crazy game with andrew and I am the crazy man.play runescape.com.done dear ronald pattinson.Get away from the keyboard, Lexie. Dad wants to write his post. Yes, now. . . . . No links Lexie, OK? . . . . Dad really needs to write his post. . . . Lexie I don't need to know about homo sapiens . . not now . . I'm trying to write something coherent. . . ."leave some stickbread for dad" . . . yes, dad needs stickbread.

Buy book, buy book, no you don't need to.That makes no sense, Andrew. See where democracy gets you? Nonsense.

On with the fun. Not that you'll be having much. It's terribly dry. Full of numbers and tables again. You'll have to wait until I've been to London for any light relief.

Get ready for dullness.

Just . . . . . . . now

It's very satisfying when theory and practice come together in perfect harmony. That happened today. The mashing section in "Brewing Science & Practice" by H. Lloyd Hind, published in 1940, agrees almost exactly with Whitbread's and Barclay Perkins brewing records.

Underlet mashing. What a fascinating topic. It seems to have been the standard method of mashing for at least the first half of the 20th century. In London. I shouldn't generalise. Still need to look at the records of some provincial breweries.

MashingWith the exception of a few specialist lager brewhouses which decoction mashed, all British breweries used an infusion mash. This method was well-suited to British malt, which was well-modified and had a low nitrogen content. Worts from an infusion were generally higher in maltose and more attenuative than those from a decoction mash.

The mash tun was first heated to close to the mashing temperature by running in hot water until it just covered the false bottom. The grist and mashing water were run through the external masher and into the mash tun. The temperature of the mashing water - the striking heat - was usually 4º or 5º F higher than the intended initial heat. Once the grist and water were "all in" the tun, the rakes were switched on to make a couple of revolutions.

What happened next, depended on if the tun was fitted with an underlet. If it were not, the mash was left to stand for 2 to 2.5 hours before sparging. If there was an underlet, the following processes occurred:

1. mashing for 15 to 20 minutes

2. mash left to stand for 30 minutes

3. water added through underlet, sometimes with the sparge running

4. mash left to stand for 90 to 120 minutes

5. taps set and spage begun

This whole procedure took 6 to 6.5 hours. Some brewers underlet twice, letting the wort stand and sparging briefly between them.

Whitbread, Fullers and Barclay Perkins employed a method very similar to the one just described, making use of the underlet to heat the mash.

Below is an example from Whitbread, mashing 86 quarters of malt.

Water was added through the underlet twice and there were two sparges. Two worts were produced which were boiled separately.

This is an example from Barclay Perkins, where 108 quarters of malt were mashed:

Just like Whitbread, Barclay Perkins underlet and sparged twice.

Mashing temperatures and mash ratesThe most important mashing temperature was the initial heat. Varying it by just a couple of degrees could have a big influence on the composition of the final wort. The ideal temperature depended on the type of beer being brewed and the malts being used. The mash rate, that is the number of barrels of water per quarter of malt being mashed, similarly varied according to the type of beer and the malts used.

Because of its lower diastatic power, mild ale malt was usually mashed at a lower temperature than pale ale malt. Grists containing large quantities of dark malts were mashed an an even lower temperature still. Beers where a high degree of attenuation was required had a lower initial mashing heat. Stock Ales, which reuired a large proportion of dextrin in the wort, were mashed at higher temperatures, even when the grist contained a great deal of dark malts.

When using an underlet, the initial temperature could be lower, which was especially useful with less well-modified malts. The underlet could then be used to raise the temperature higher than would normally be used as an initial heat. The production of maltose could be affected by the timing and temperature of underletting. The longer the mash stood before underletting, the greater the amount of maltose produced.

The table below gives typical mashing temperatures for various types of beers. These were not set in stone, but could vary depending on other factors such as the characteristics of the malt and the equipment in the brewery.

These are the Barclay Perkins mashing temperatures from the mid-1930's.

As Hind stated, Stock Ale (KK) and Pale Ale had the highest temperature, Mild (XX, X, A) a rather lower one and Stout (BS, OMS, TT) the lowest of all. Though the range spanned by the different beers is smaller than Hind suggested, with onlt 4º F between the warmest and coolest.

Sources:

"Brewing Science & Practice" H. Lloyd Hind, 1940,

Whitbread and Barclay Perkins brewing records..

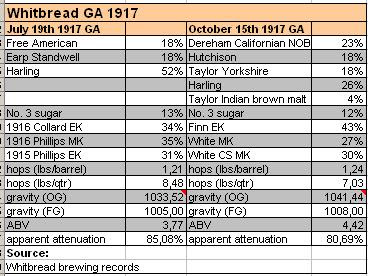

Breweries are a conservative bunch. Their recipes don't usually change much from one year to the next. Wartime is an exception. Shortages and government interference forced breweries to modify their recipes sometimes as often as every week or two. 1917 to 1919 was one such period. 1942 to 1943 is another.

Breweries are a conservative bunch. Their recipes don't usually change much from one year to the next. Wartime is an exception. Shortages and government interference forced breweries to modify their recipes sometimes as often as every week or two. 1917 to 1919 was one such period. 1942 to 1943 is another.

just as in the interwar period, the only other adjunct was maize. In 1940 this was replaced with rice. In 1941, there was neither rice nor maize. Both flaked and torerefied barley were introduced in 1942.

just as in the interwar period, the only other adjunct was maize. In 1940 this was replaced with rice. In 1941, there was neither rice nor maize. Both flaked and torerefied barley were introduced in 1942.