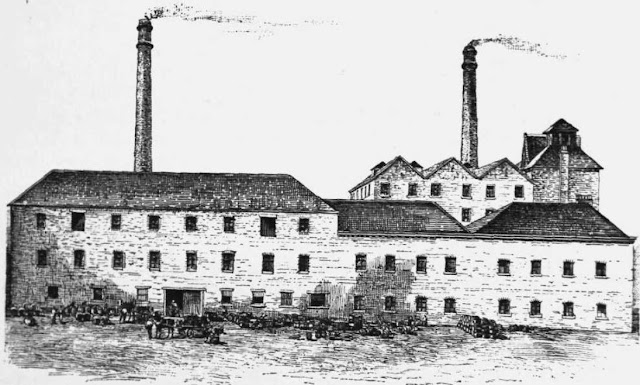

As a relief from tables full of beers details, I'm making a small detour to Barnard, chronicler of Britain's breweries at their late 19th century peak. First we'll look at one of the less fashionable Youngers, George of Alloa.

Brewing is a funny industry. Sometimes it settles in obvious places, such as large population centres, like London or Edinburgh. Others it pops up in seemingly random small towns such as Burton, Alton, Newark-on-Trent and, where we'll be today, Alloa. Water is usually cited as the reason for these strange sitings. And it certainly played a part in the case of all the examples I've quoted. All had the gypsum-rich water demanded for Pale Ale brewing.

Though George Younger had been knocking around since the mid 18th century, mostly brewing strong Alloa Ales, their business only boomed when they got into Pale Ale. They were quick to spot the domestic market for Pale Ales and were one of the first Scottish brewers to brew them in a big way.

Introduction over, let's see how they mashed.

"By the advice of our guide, we proceeded to the mashing-stage on the first floor of the brewhouse, passing through the Excise office to see the grist-hoppers, two in number, depending over the mash-tuns, and capable of holding 100 quarters; the crushed malt being delivered thereto by a Jacob's ladder. The hoppers are constructed of timber, stained and varnished, each being lined with zinc. The mashing-stage covers nearly half of the first floor of the brewery, and is 60 feet in length. It contains three domed mash-tuns, constructed of cast-iron, lagged and encased with match-boarding, which is stained and varnished. The mashing capacity of these tuns is 100 quarters, and they all contain the usual draining plates, mashing gear (driven by steam-power), and overhead revolving spargers. All the tuns are commanded by Steel's mashing machines, which are for saturating the malt and water, at a heat of about 150 degrees, or thereabouts, according to the lightness or heaviness of the malt, and this brings us to the subject of liquor or water, which plays such an important part in brewing. It may be as well to explain, that the water for brewing is obtained from a deep well in the north yard, which is excavated 100 feet, and bored to a depth of 300 feet There are also four other wells on the premises, used for different purposes. The storing tank is placed at the top of the brewery and commands a large malleable iron water heater, lagged with composition and heated by double furnaces. It is placed in a brick built room 50 feet long, on the south side of the copper hearth, and has a capacity of 300 barrels. On the copper hearth there are two more heaters, both used for heating mashing water, and containing together 400 barrels."A mash tun with a 100 quarter capacity gives you a brew-length of approximately 400 barrels. Have three such tuns and you've a daily capacity of 1,200 barrels. Or an annual capacity of 360,000 barrels. That would put George Younger easily in the top 20 biggest breweries in the UK.

"Noted Breweries of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 2", Alfred Barnard, 1889, page 437.

The kit is pretty standard. Cast-iron vessel insulated with wood; Steel's masher (that's the external screw that mixes grain and hot water on their way into the tun), internal mashing rakes and a sparger.

It may seem odd that there were two different types of mashing machine. Internal rakes had been the first type of mashing machine, inventd in 1807, it mechanised the mixing of grain and malt which until then had been performed by men with paddles. Must have been great fun in a tun containing hundreds of barrels.

Steel's masher, or the external masher, was invented in 1853. It gives a much more consistent mix of grain and water and does it as they both enter the tun. Such a good design that it's still in wide use today. So, if the mixing has been done before the grain has even got into the tun, why still have internal rakes?

Two reasons. First, for underletting. The standard late 19th century way of mashing was mash, underlet, sparge. Underletting, or introducing hot water from the bottom of the tun, was a way of doing a simple step mash. After underletting the rakes made a couple of revolutions to mix the hot water thoroughly into the mash. Second, to loosen a stuck mash.

See what Barnard has to day on this subject:

"The object of the rakes, or internal machine, inside the tuns is to stir the "goods" or mash, to make them homogeneous as to consistency and it is useful for the draining operations afterwards. We noticed also that the tuns are each tapped by several cocks placed in the bottom of the mash-tun, the object being to secure an equal outflow. The sparging is to sprinkle the goods evenly all over for the purpose of still further securing this object. When the tuns are drawn off, the grains are made to fall through spouts direct into the farmers' carts, which are drawn up in the grains' shed beneath."

"Noted Breweries of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 2", Alfred Barnard, 1889, pages 437 - 438.

Sparging was, of course, initially a purely Scottish practice. I don't think Barnard has quite understood its purpose, which is really to extract sugars left in the grains after running off the first wort.

That was so much fun I'm going to do it all over tomorrow. Except then we'll be discussing boiling. Can't wait.

4 comments:

Great summary of how industrial scale mashing for the uninformed like what I am.

Were mash kettles of the period directly fired? If so, a possible third reason for the internal rakes would be to prevent the mash at the bottom of the tun from scorching if the kettle temperature was raised during step mashing or mashout.

Thomas Barnes, no they weren't directly fired. That's why they had to underlet to raise the temperature of the mash.

They weren't generally heated at all, were they? One of the major differences between British and German brewing technology.

Post a Comment