I've just published my second book this week. Is that a record?

This one is a couple of years' wort of travel reports. I hope it does as well as the first two volumes. Between them, they've sold almost three copies.

I've just published my second book this week. Is that a record?

This one is a couple of years' wort of travel reports. I hope it does as well as the first two volumes. Between them, they've sold almost three copies.

I’m going to limit myself here to versions brewed in Berlin. Yes, I know many, quite possibly hundreds, are brewed in the USA, to varying degrees of authenticity. But I’m going to stick to those brewed in the style’s home city.

Berliner Weisse is the best-known German sour beer, which is somewhat ironic given that it’s virtually extinct in its home city. There’s currently only one example really brewed on a large scale: Kindl. And that’s crap.

In 2010 just 10,180 hl of Berliner Weisse were sold in the off trade , meaning total output couldn’t have been more than 20,000 or 25,000 hl.

In the late 1980’s there had been three different Berliner Weisses brewed: East Berlin Schultheiss, West Berlin Schultheiss and West Berlin Kindl. First West Berlin Kindl bought East Berlin Schultheiss and closed it. Then West Berlin Schultheiss and Kindl merged and the Schultheiss Berliner Weisse was dropped. Which was really annoying because the Kindl was by far the worse of the two.

But . . . there are more authentic versions being brewed, albeit on a fairly small scale. Better than nothing, I say.

That was an extract from my recently published book on Berliner Weisse, "Weisse!"

This recipe is based on a description in "Die Fabrikation obergäriger Biere in Praxis und Theorie" by Grennell.

The book describes four different ways of brewing Berliner Weisse, this is method II. It differs considerably from Schönfeld’s procedure. For a start, half of the wort is boiled during the decoction. The hops were added during the decoction rather than to the mashing water.

As always, some time secondary conditioning is required to bring out the required Brttanomyces character. A minimum of four weeks, longer if you like your beer with more bite and funk.

| 1907 Berliner Weisse (Schankbier) | ||

| wheat malt | 5.25 lb | 75.00% |

| lager malt | 1.75 lb | 25.00% |

| Hallertau 30 mins | 0.50 oz | |

| OG | 1032 | |

| FG | 1007 | |

| ABV | 3.31 | |

| Apparent attenuation | 78.13% | |

| IBU | 5.5 | |

| SRM | 2.5 | |

| acidity (pH) | 3.63 to 3.73 | |

| Mash single decoction | ||

| Boil time | 30 minutes | |

| pitching temp | 60º F | |

| Yeast | Wyeast

2565 Kölsch lactobacillus delbruckii Brettanomyces bruxellensis |

|

Yes, after a couple of weeks of not really all that intensive work it's done. My book about Berliner Weisse is finished and published.

99 pages of Berliner Weisse fun, tracing the history of the style from the 18th century to today. Including a look at Weisse from both sides of the Berlin wall. As an extra special bonus there are 19 historic recipes hand crafted by me.

It's easily the best book in English about Berliner Weisse*

* I'm pretty sure it's the only one.

How common was Porter in the DDR? Not that common, to be honest. I think i saw it in a shop once. Almost certainly in Berlin. Because that's where all the nice things went.

That said, it was sufficiently widespread for it to feature in all the standards documents. The one on ingredients specifically mentions Brettanomyces. Which a 1950s DDR brewing textbook suggested should be pitched in Porter for secondary conditioning.

The quantities produced was probably pretty small. But a surprising number of breweries made one. I know that from my DDR label collection. At least 15. That's how many I have labels from. I'm sure that there more quite a few more than that.

These are the 15:

Berliner Kindl

Braugold

Dessau

Eberswalder

Eibauer

Grabower

Greussen

Meisterbräu Halle

Lübzer

Magdeburg

Riebeck

Rose-Brauerei Grabow

Sternburg

Hochschul

Meininger

It's weird how Deutscher Porter as a style seems to have been almost totally forgotten. Even though it was brewed until around 30 years ago. They all seem to have been discontinued soon after reunification. Either that, of the breweries simply closed. A few did reintroduce beers called Porter, but they were totally different in style. Much weaker and really sweet. Pretty awful, the ones I've tried.

Here are the labels:

I've learnt quite a bit. Enough to change my opinions on some topics. Or at least have a more nuanced approach. The level of sourness being a big one. You'll need to buy the book if you want to learn all the details.

In the meantime, here's a description of the brewing process at one Berlin brewery between the was.

In the kettle, the malt was doughed in with water at 30º C. The temperature was slowly raised to 53º-54º C where it was held for 30 minutes for a protein rest.

The temperature was raised to 75º C by which time saccharification should have occurred.

A third of the wort was transferred to the lauter tun and the remainder of the wort in the kettle brought to the boil.

After boiling for 30 minutes, it was mixed with the other third of the wort in the lauter tun, making sure the temperature didn’t exceed 76º C. The mixture was left to stand for 40 minutes before running off.

The clear wort was returned to the kettle and brought to 95º C for 15 to 20 minutes. Then immediately cooled to 18º C.

The wort was pitched at 16º C and after four days the temperature rose to 20º C. When it had dropped back down to 16º C, primary fermentation was done.

1º to 1.25º Plato gravity needed to be left for bottle conditioning. If not, Frischbier needed to be added to raise the gravity to the required level.

"Die Herstellung obergärige Biere und die Malzbierbrauerei Groterjan A.G. in Berlin" by A. Dörfel, 1947 pages 12 - 14.

I found it in a book about the architecture of Berlin. There's a section on breweries which has some dead useful information. For me, at least.

In the late 1880s and early 1890s, around two thirds of Berlin’s breweries were top fermenting, but they only produced one third of the beer. The table below lists all top-fermenting breweries which did not all necessarily brew Weissbier.

Intriguing that more new top-fermenting breweries were arriving than bottom-fermenting ones: 27 compared to 8. Though that’s probably due to Lager breweries operating on a larger scale and requiring more capital to set up.

It’s hard to see any trends in the production figures.

Remember that there were several other top-fermenting styles in Berlin: Braunbier, Porter, Bitterbier. The quantity of Weissbier brewed was lower than the number in the table, which is for all types of top-fermented beer.

There’s no discernible shift from top to bottom fermenting that I can see. The proportion is always around one third to two thirds. Though it’s clear that the bottom-fermenting breweries were on a larger scale.

The difference in scale only became larger over time.

The average output of a top-fermenting brewery remained rooted at 20,000 hl. While that of bottom-fermenting breweries increased by more than 50%.

| Number of Berlin breweries 1872 - 1894 | |||||

| Year | Bottom fermenting | Top fermenting | Total | ||

| 1872 | 21 | 43.75% | 27 | 56.25% | 48 |

| 1888/89 | 26 | 36.62% | 45 | 63.38% | 71 |

| 1889/90 | 26 | 34.67% | 49 | 65.33% | 75 |

| 1890/91 | 27 | 36.00% | 48 | 64.00% | 75 |

| 1891/92 | 27 | 35.53% | 49 | 64.47% | 76 |

| 1892/93 | 29 | 38.16% | 47 | 61.84% | 76 |

| 1893/94 | 29 | 34.94% | 54 | 65.06% | 83 |

| Source: | |||||

| Berlin und seine Bauten, Architecten-Verein zu Berlin, Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn, Berlin, 1896, page 648. | |||||

| Output of Berlin breweries 1872 - 1894 | |||||

| Year | Bottom fermenting | Top fermenting | Total | ||

| 1872 | 898,049 | 62.89% | 530,000 | 37.11% | 1,428,049 |

| 1888/89 | 1,858,530 | 64.21% | 1,036,058 | 35.79% | 2,894,588 |

| 1889/90 | 1,891,693 | 63.95% | 1,066,378 | 36.05% | 2,958,071 |

| 1890/91 | 1,939,023 | 64.66% | 1,060,001 | 35.34% | 2,999,024 |

| 1891/92 | 1,936,987 | 67.62% | 927,678 | 32.38% | 2,864,665 |

| 1892/93 | 2,116,979 | 67.95% | 998,661 | 32.05% | 3,115,640 |

| 1893/94 | 1,988,179 | 63.87% | 1,124,491 | 36.13% | 3,112,670 |

| Source: | |||||

| Berlin und seine Bauten, Architecten-Verein zu Berlin, Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn, Berlin, 1896, page 648. | |||||

| Average output of Berlin breweries 1872 - 1894 | ||

| Year | Bottom fermenting | Top fermenting |

| 1872 | 42,764 | 19,630 |

| 1888/89 | 71,482 | 23,024 |

| 1889/90 | 72,757 | 21,763 |

| 1890/91 | 71,816 | 22,083 |

| 1891/92 | 71,740 | 18,932 |

| 1892/93 | 72,999 | 21,248 |

| 1893/94 | 68,558 | 20,824 |

| Source: | ||

| Berlin und seine Bauten, Architecten-Verein zu Berlin, Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn, Berlin, 1896, page 648. | ||

How sour should it be? That probably depends on how long you age it. Bottle-conditioning for at least a couple of weeks is the way to go.

| 1834 Berliner Weisse | ||

| smoked wheat malt | 7.50 lb | 75.00% |

| lager malt | 2.50 lb | 25.00% |

| Hallertau 15 mins | 1.25 oz | |

| OG | 1045 | |

| FG | 1021 | |

| ABV | 3.18 | |

| Apparent attenuation | 53.33% | |

| IBU | 13 | |

| SRM | 3 | |

| Mash single decoction | ||

| Boil time | 15 minutes | |

| pitching temp | 66º F | |

| Yeast | Wyeast

2565 Kölsch Lactobacillus clausenii Brettanomyces clausenii |

|

| action | temperature | time (minutes) |

| Mashed in | 100º F | 30 |

| first rest | 133º F | 30 |

| deoction with hops | 15 | |

| mash out | 167º F |

He was keen that Berlin brewers adapted his method, which he claimed produced a better and more stable beer, so they could see off the threat of Bavarian beer, i.e. Lager. He can't have had much success, as Berlin brewers were still decocting their Berliner Weiss 150 years later.

Mash in 2,887.5 kg wheat malt and 412.5 kg barley malt with 2,404.5 litres of water at 45º to 50º C.

While the water and malt were being mixed, water was brought to the boil in the kettle. This was slowly mixed into the grains in the mash tun, every five minutes adding more water. The temperature was taken regularly to see if the mixture had reached 65º to 67.5º C, which should occur when almost all the water from the kettle. In total, 3,206 litres of boiling water.

In winter, the mash was left to stand for 30 minutes, covered. In summer, 60 minutes, uncovered.

The mash tun was tapped and, when the wort began to run clear, it was pumped to the kettle. When the kettle was half full, between 122 gm and 176 gm of hops per 55 kg of malt were added. By the time it came to the boil, the kettle was full.

The wort was boiled for 20 to 30 minutes, then was filtered through a hop basket into the cooler.

More water (3,206 litres) was brought to the boil and slowly mixed with the grains. When all the boiling water had been added, the mash should be at 63.75º to 65º C. It was stood for 30 minutes in summer, 60 in winter.

It was drawn off and boiled in the same way as the first wort, that is, for 20 to 30 minutes. After which it went to the cooler.

Recommended was to have two coolers allowing both worts to be cooled at the same time and blended together when the yeast was pitched. Though in winter, you could just throw the second wort into the cooler with the first wort.

There was a third charge of cold water, stood for 30 to 60 minutes, for Kovent.

"Handbuch der praktischen Bierbrauerei" by Dr. Julius Ludwig Gumbinner, 1845, pages 234 - 237.

All this and much more, will be in my book "Weisse!", which should be available soon. I just need to finish writing it.

A reader pointed out that some of the links to my many, many books were broken. The bastards at Lulu, sorry, the very nice people at Lulu, had changed the URLs of the pages. Don't remember them telling me that. Maybe I missed it.

I've no idea how long the links were broken. Or how many sales I've lost. Probably not that many, as no-one mentioned it until now.

I've fixed the links now. So order away. Buy my books!

Especially this classic. I think total sales are now almost in double figures after a recent surge ( one sale).

I've noticed changes in my pub-going habits over the years. It's not just the frequency of visits. It's also their timing.

I rarely go for evening sessions any more. Only when on holiday, really. Because I far prefer afternoons. For a variety of reasons. Pubs are less crowded, transport is easier and can gave a few hours relaxing at home before heading off to bed.

When the kids came along, I'd give Dolores a little relief by dragging them down the pub in the afternoon. How many happy hours I've spent chasing Andrew down Nieuwe Dijk after he'd made a dash for freedom from Café Belgique. Now I have to drag him out of the pub. "Can I have another beer, dad?" is his catchphrase.

During one of my periods of unemployment, I filled the days working on my European Pub Guide. Part of the project was documenting areas outside the city centre. Which entailed afternoon expeditions with anti-American Mike. Usually kicking off between 13:00 and 16:00, depending on when the pubs opened.

I'm down to one weekly pub excursion: Saturday afternoon in Butcher's Tears. And I'm always back in time for my tea.

| 1913 Boddington BB | ||

| pale malt | 8.25 lb | 80.49% |

| flaked maize | 1.00 lb | 9.76% |

| No. 3 invert sugar | 1.00 lb | 9.76% |

| Cluster 135 mins | 0.50 oz | |

| Fuggles 60 mins | 0.50 oz | |

| Goldings 30 mins | 0.50 oz | |

| Cluster dry hops | 0.125 oz | |

| Goldings dry hops | 0.25 oz | |

| OG | 1048 | |

| FG | 1016 | |

| ABV | 4.23 | |

| Apparent attenuation | 66.67% | |

| IBU | 22 | |

| SRM | 9 | |

| Mash at | 152º F | |

| Sparge at | 165º F | |

| Boil time | 135 minutes | |

| pitching temp | 61.5º F | |

| Yeast | Wyeast 1318 London ale III (Boddingtons) | |

We've bot past the mashing section and are now looking at the remainder of the process. This time there are some temperatures given. Even though the brewery in question didn't seem to believe in them, relying instead on the ever-so-reliable finger method.

After standing, the wort began to be drawn off. At first the tap was only opened a little and the wort returned to the top of the filter tub until it began to run clear. The tap was then opened wide and the wort run off into the grant and from there pumped to the cooler. When the wort started to become cloudy again the tap was closed.

Meanwhile the kettle had been refilled with water and brought to the boil. This was now poured over the grain bed in the filter tun. This was left to stand without being touched for around 30 minutes.

The kettle had meanwhile been refilled and brought to the boil again. The boiling water was added to the filter tub and left to stand for another 30 minutes.

The first wort was now returned from the cooler to the cleaned mash tun and the second wort transferred to the cooler.

When the first wort reached a temperature of 27.5º to 30º C, some of it was drawn off and mixed with yeast. The yeast mostly came from a previous brew, but twice in the week yeast shipped from Cottbus was used.

After about an hour this wort started to ferment and it was mixed with the first wort in the mash tun, which was now about 22.5º C.

When fermentation of the first wort had kicked off, after 6 to 8 hours, the second wort was added. This new mix started to ferment after around an hour. It was then filled into barrels and immediately shipped out to publicans.

What little fermenting wort remained was transferred to barrels in the fermentation cellar. Fermentation was completed in 18 to 20 hours.

A third addition of cold water was poured over the grain bed and left to stand for between 30 and 60 minutes. This was drawn off, pitched with yeast and sold to the poorer classes as Koventbier. Fermentation was completed in their home. To make it more palatable, it was often mixed with some strong Weisse before bottling.

"Handbuch der praktischen Bierbrauerei" by Dr. Julius Ludwig Gumbinner, 1845, pages 225 - 230.

Once again, the wort was pitched in the mash tun. Note that the majority of even the primary fermentation was performed by publicans. Only a small amount was fermented in the brewery itself.

When I was at university I went to the pub most days. Sometimes twice, afternoon and evening sessions. The first in the student union bar, the second in the Cardigan Arms.

Swindon was surprisingly good for pubs. And beer. Which encouraged me out quite often. Though less than in my single days. Drinks sometimes on a Friday lunchtime with colleagues. The odd time after work. Every now and again the odd pint in the pubs on our estate. Weekend evenings in the Old Town drinking Morrels and Wadworth. Or down the railway Village for Archers.

Settling in Amsterdam, pubs might be on the cards a couple of times a week.At least the first time around.

Melbourne revived the pub man in me. I dropped by the Canada most days on the walk home from work. Just to cool down. With a schooner of Cooper's Stout. Plenty of visits later in the evening with Dolores.to the local pubs with draught Coopers.

Definitively back in Amsterdam, pubs played prominent role again. At least three or four sessions a week.Saturday and Sunday Happy Hour in Rick's Café. A few jars in Café.Belgique once or twice a week.After the kids came along, I'd take them to the pub on weekend afternoons. Café Belgique if I could be arsed to go into town. Bedier if I couldn't. Evening sessions were pretty much a thing of the past.

When the kids became teenagers, the afternoon sessions dried up. What was left? The odd evening with mates.

Now I'm down to once a week. Saturday afternoon with Andrew and the lads down Butcher's Tears. And that's it, pretty much.

Why do I visit pubs so much less? Part of it is just being at a different stage of my life. But money has a lot to do with it, too. A couple of drinks each for me and Dolores can top 30 euros. I can't afford to do that six or seven times a week.

When I started drinking, it was almost exclusively in pubs.This may seem strange to those not quite as ancient as me, but beer used to be cheaper in pubs than in shops. I almost never drank at home just for that reason. Plus bottled beer was way inferior to a good pint of cask.

The latter consideration might also play into Dutch pubs being less attractive. In the UK, cask will tempt me into a pub. While here pubs don't sell anything better than the Abt I drink at home.

It's quite different from another description I have from just a couple of years earlier. Why is that? Because every brewery seemed to have their own process. This is just a description of one of them.

It's quite a complicated mashing scheme with three decoctions.All of the thick mash.

Seven parts wheat malt to one part barley malt was used. The malt having been dried on an English style malt kiln using indirect heat at a low temperature to keep the colour as pale as possible. The brewery whose process was being described kept their malt for at least a year before brewing with it.

The kettle was filled with water, once it had been brought to the boil, it was transferred to the mash tun. Cold water was added until the mixture was lukewarm. The brewer judged when the correct temperature had been reached with his finger.

The grain was added to the mash tun and mixed with the water for around 30 minutes until it had a smooth, even consistency.

The kettle was refilled while the mash was being stirred and when it had boiled was gradually added to the mash tub. The mixture was stirred with mash paddles until the consistency was even.

The mash was left to rest for 30 to 45 minutes while another lot of water came to the boil in the kettle. This was gradually mixed into the mash, except for around 20%, which was left in the kettle.

Between 122 gm and 176 gm of hops per 55 kg of malt were added to the water left in the kettle and boiled for around 10 minutes.

Some of the mash was transferred to the kettle and brought to the boil. When it started to boil, more mash was added. This was boiled for around 10 minutes.

The boiled mash and hops was mixed back into the main mash in the mash tun. After a good mix, some mash was transferred back to the kettle and brought to a boil again.

This second decoction was returned to the mash tun and mixed in. After which, some more mash was moved to the kettle and boiled.

After boiling it was transferred to the filter tub at the same time as the main mash and the two were mixed. Meaning mashing out happened here and not in the mash tun.

"Handbuch der praktischen Bierbrauerei" by Dr. Julius Ludwig Gumbinner, 1845, pages 217 - 225.

Once again, mash out was in the filter tub rather than the mash tun.

| 1913 Boddington B | ||

| pale malt | 6.75 lb | 81.76% |

| flaked maize | 1.00 lb | 12.11% |

| No. 3 invert sugar | 0.50 lb | 6.06% |

| caramel 2000 SRM | 0.006 lb | 0.07% |

| Strisselspalt 120 mins | 0.50 oz | |

| Fuggles 60 mins | 0.25 oz | |

| Goldings 30 mins | 0.25 oz | |

| Goldings dry hops | 0.25 oz | |

| OG | 1037 | |

| FG | 1010 | |

| ABV | 3.57 | |

| Apparent attenuation | 72.97% | |

| IBU | 13 | |

| SRM | 7 | |

| Mash at | 152º F | |

| Sparge at | 161º F | |

| Boil time | 120 minutes | |

| pitching temp | 62.5º F | |

| Yeast | Wyeast 1318 London ale III (Boddingtons) | |

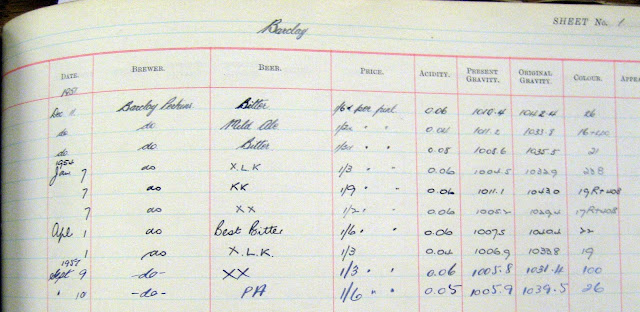

What a wonderful document it is. Well, pair of documents, as there are two volumes. The most valuable references for anyone wanting to take a close look at British beer in the 20th century. I don't know what I would have done without it.

Across thousands of entries, it records the vital statistics of the beers of Whitbread's rivals. OG, FG, price, colour. Sometimes even short descriptions of flavour, condition and clarity. There's an emphasis on the London area, which was Whitbread's main stomping ground. But plenty of beers from all parts of the UK.

Between them, the two volumes cover a span of almost 50 years: 1922 to 1968. Starting with the fallout of WW I and ending in the keg era, there were a lot of changes over those years. All of which you can see reflected in the Gravity Book's pages. For example, laying bare what bad value keg beer was in comparison to cask.

I've lent heavily on the Gravity Book for a couple of my works: Austerity! and Blitzkrieg!. One, Draught!, is totally dependent on it.

While writing the last-named book, I got a better idea of why Porter was in terminal decline between the wars. It was quite often in poor shape, described as "sour" or "going off". Sounds like cask beer that's been on for too long. Poor sales meaning beer gets too old, leading to even fewer sales. A vicious cycle, such as happened with Mild a few decades later.

When it becomes particularly useful is in relation to breweries whose records have been lost. Allowing us our only glimpse at what their beers were like.

I've transcribed every entry into a spreadsheet. Except for a couple of pages where my photos are too blurred to read. It took a lot of hours. Worth it, totally. Not sure I'd want to do it again.

|

| a Barclay Perkins page from volume 2 |

For the moment, the Gravity Book volumes are in a safe place: London Metropolitan Archives. But you have to physically go there to access them. A pretty big limitation.

How could I forget my book Numbers!. Which has hundreds of analyses taken from the Whitbread Gravity Book. As well as other sources.

It wasn’t just fry-ups and pies in Folkestone. I’m classier than that. Much classier.

The breakfast Yorkshire puddings were a bit of a let-down. My hopes had been so high. Would the next lot be better? You’ll find out later. As that was our last meal. I’m trying to keep some sort of chronology going here.

I’m a very undemanding travelling companion. As long as I’m getting regularly served with beer, I’m happy. I’d only made one request of Mikey: "I'd like a curry." OK, was his reply.

Not remembering having seen a curry house while wandering around that I could recall, I resorted to the internet. A Nepalese place called Annapurna caught my eye. Fairly cheap and interesting looking food. Plus it was just off the main drag, on the way to the East Kent Arms.

We rolled on down there around 6 PM. Pretty early. Early enough for there to be plenty of free tables. Obviously, we kicked off with some beer. Some Nepalese brand, I think. Probably brewed in Bedford or Bury St. Edmonds.