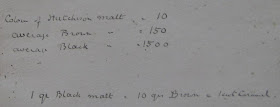

I found it in the Whitbread Ale log for 1918 - 1919. Why they should have stuff about brown and black malt in an Ale log is a bit of a puzzle. They didn't use either in their Ales, just their Porters and Stouts.

The numbers look like degrees Lovibond 1 inch cell to me. Which puts Whitbread's brown malt bang inbetween the two samples detailed by H. Lloyd Hind ("Brewing Science & Practice", 1943, pages 275-276), They were 102 and 212. Whitbread's black malt had the same colour as the darkest Hind's samples.

The last line shows just how far a little black malt goes, colour-wise. One quarter (approx. 224 pounds) is the same as 10 quarters of brown malt and a hundredweight (112 pounds) of caramel.

When Britain attempted to go metric, I thought all those weird weights and measures I'd had to learn as a kid would to of no further use. How wrong I was.

I wonder why black malt couldn't equal brown if the right amount was used, i.e., in flavour too. Could brown malt have been persisted with just from tradition, until finally it was seen it wasn't necessary? Wasn't it Stopes who called brown malt a historical anachronism?

ReplyDeleteThe only way to know for sure would be to taste a beer made from 100% brown malt or at least one of the mid-1800's grists, which used a large amount of that material.

I am not sure I have ever had a beer like that. Rauchbier in Bamberg, made from malt kilned over beech wood (as some brown malt was in England), is incredibly smoky. Can porter have tasted like that originally and into the mid-1800's? This seems unlikely to me, in part because so many observers stated that malt should not absorb the smell of the fuel it is kilned with.

Who has tasted porter made all or partly from pale malt blistered brown (a relatively fast procedure) over oak or beech wood? I had Alaskan Smoked Porter many years ago, made from malt kilned on alder, it was interesting but not like Rauchbier as I recall, and certainly within the flavour range of good porter as most here would know it.

Have you created any 1700's or mid-1800's porters, Ron, or has anyone else? I think it should be relatively easily to copy the brown malt method in the old books, i.e., blister-up some pale malt in an improvised barbie using oak chips.

I need to know what porter was like originally, or at least mild porter, Maybe it tasted like Lion Stout. (I think if they were lucky it did!).

Gary

They are more or less the same as today. In my brewing software I have brown malt set to 150 and black malt 1300. There are very wide tolerance spreads on black malt anyway. Dunno what Hutchison malt is - probably what today would be called mild ale malt.

ReplyDeleteAt least it is now clear that the brown malt used by Whitbread was drum brown.

It seems that the last batches of F&J wood-dried brown malt did go to Mackeson in the 1950s. I was rather hoping that Whitbread had clung onto it for a lot longer in their porter.

They were quite likely to have used a bit of black malt in their cooper for final colour adjustment, even in an ale.

Graham, Whitbread used caramel for colour adjustment. After WW II they dropped black malt altogether, using a combination of pale, brown and chocolate in their Stouts.

ReplyDeleteGary, brown malt has a distinctive taste.

ReplyDeleteI'm still uncertain in my as to how brown malt was made in the 18th century. It has to be different from later versions, because it had diastatic power.

Not recreated any Porters that old yet. Though that may change soon . . .

Ron, I think the early brown had enough diastase because the malt was only blown or blistered. In the kernel of the malt corn there was essentially what one finds in pale malt. Some of the diastase and sugar were destroyed but not all.

ReplyDeleteI think later, if brown malt lost all diastatic power, it was because it was roasted for longer and all the enzyme and incipient sugars were destroyed. Why would they do that? I think to get the colour, and some of the old taste, they wanted and to compensate for the large amount of pale in the grist. This seems to be equal in function to black patent malt but the latter is not kilned over an open fire.

This may be why a modified form of brown malt continued to be made, to impart a smoky acrid tinge. The final "brown malt" (caramel and Munich malt and similar) would impart no such flavours due to the well-known stewing effect of such manufacture.

Yet, black patent can impart smoky and burned tastes, this seems evident from many craft porters today. Perhaps there are different ways to make such malt to make its effect similar to the original and 1800's-1950's forms of brown malt.

Gary

"Gary, brown malt has a distinctive taste."

ReplyDeletevery true, there is no other malt that tastes like it, even with the modern stuff

"Not recreated any Porters that old yet. Though that may change soon . . ."

Sounds promising

I have made a porter with 100% brown malt that I made. still had DP and was very different than the Stitch I made with 100% crisp brown malt (use exogenous enzymes). The smoke wasn't overpowering but it was there. Lacked a lot of what we think of as porter character. More of a toasted character with the roast more like black malt. Not overwhelming by any means but just a light dark fruit not cocoa, chocolate, or the like.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting, thanks, Kristen.

ReplyDeleteGary

Ron, here is a simple recipe for an 1829 porter (from pg. 65) designed for small amounts.

ReplyDeleteNot only that, the brewer advises how to make your own porter-malt.

This is therefore ideal for reproduction on a small scale.

This would be a good and early-style porter to do. It uses only brown malt and amber malt, a rich mixture as we know from John Tuck and many other sources, and is intended to deliver the old flavour.

http://books.google.com/books?id=8aw3AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA65&dq=John+Ham+porter-malt&cd=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false

Gary

"I think later, if brown malt lost all diastatic power, it was because it was roasted for longer and all the enzyme and incipient sugars were destroyed. Why would they do that? I think to get the colour, and some of the old taste, they wanted and to compensate for the large amount of pale in the grist. This seems to be equal in function to black patent malt but the latter is not kilned over an open fire.

ReplyDeleteThis may be why a modified form of brown malt continued to be made, to impart a smoky acrid tinge. The final "brown malt" (caramel and Munich malt and similar) would impart no such flavours due to the well-known stewing effect of such manufacture.

Yet, black patent can impart smoky and burned tastes, this seems evident from many craft porters today. Perhaps there are different ways to make such malt to make its effect similar to the original and 1800's-1950's forms of brown malt."

You really have lost me here - have you got anything to back any of this up with? I mean, where are you coming from here?

I can back it up with this. Many period reports, pertaining to manufacture of brown or blown malt, indicate that you start with pale malt. I cited one such example which offers a simplified way, for a home brewer (in John Ham's book, I gave the link) to make such malt.

ReplyDeleteYou take the pale malt and put it in a 3 inch layer on a baker's kiln (generally wood-fired then). He advised to take it out after 30 minutes, which would have been variable, but the idea is clearly conveyed.

Ham then advises to blend that malt with amber malt to make porter.

That pale malt became darkened and the skin of the barley corn detached and puffy or blown. But the starch and enzymes were not completely destroyed, that brown malt can become beer. This is evident from his recipe and also those in John Tuck where he explains the differing results of efficiency and colour you get from combining less-effective brown malt with pale and/or amber.

Another contemporary source states that such malt had 34% less efficiency than pale malt (I believe it was Watkins). If you read Tizard, John Tuck, John Ham, Thomson & Stewart, Watkins, they all state the same thing essentially. (All on Google Books0.

So, in the 1700's when porter "started", all blown or brown malts would have been used, and yields would have been low and inconsistent. As indeed these later authors state.

Later in the 1800's, it is evident that brown malt lost most ability or all to turn to fermentable sugar and alcohol. This is because, I infer, it was processed for many hours on a kiln (up to 6, some accounts say). The starch and enymes in the kernels were carbonized. This malt imparted colour and some flavour only but no extract, it could not contribute to alcohol yield.

Kristen was referring to these two forms in his recent comment where he stated the latter type was "crisp" and the former was not, it was not toasted as much, essentially.

Stopes gives a good historical look back from the later 1800's.

All the sources are viewable in full or mostly on Google Books.

For this kind of opinion, I cannot always cite textually where someone said exactly what I am saying. It is an opinion, a interpretation of historical materials, based on reading many sources in this area.

Gary