I awoke Sunday hangover-free. I suppose those tiny beer festival measures did have some advantages. Early, too. Just as well. Mike knocked on my door at 08:30.

He'd been drooling over the smørrebrød shop since we arrived. But he hadn't caught it open. I must admit, the open-topped sandwiches in the window did look very appealing. Which is why I'd checked the opening times, very conveniently posted on the door. They opened at 10:00 on Sunday. Until then we had to make do with a litre of coffee from the Seven Eleven.

Lack of Danish language skills meant Mike had missed out on the meal he'd set his heart on. The big lump of meat with boiled spuds everyone in the Mad Telt had been eating. He ended up with goulash instead. He was determined to avoid smørrebrød disappointment.

Fakta

FaktaThe low-budget Fakta just around the corner opened at 10:00, too. At 09:58 we joined the group of change-janglers with their noses pressed against the door. It was a surprisingly large group. At 10:04 they still hadn't opened. I sensed Mike's unease. He might have to wait until 10:15 for his smorrebrod.

As usual, I headed straight for the beer section. Fakta is like Aldi or Lidl, with the stock still in boxes. My hopes weren't high. What did I find? Only Fuller's 1845. In Amsterdam only the two specialist beers shops,

Bierkoning and

Cracked Kettle, sell it. And this pretty basic, suburban, small supermarket had it. The eye-watering price made me feel a bit better, but I still had a nagging feeling I'd chosen the wrong country to live in.

Mike was on the look out for a present for his wife. A food-themed present. Unfortunately all the possibilities were jars with liquid in them. A no-no when you're travelling with just hand baggage, due to those stupid security rules about liquids. That's why I hadn't brought any of my beer with me. And why I wasn't taking any beer home.

So what was I doing in the beer section, if I wasn't looking for souvenirs? On the look out for something to accompany breakfast. Nothing too heavy. More a toothbrushing sort of beer. You know, something that won't strip the enamel off your teeth or leave your tongue feeling like it's been shaved.

Refsvindinge Ale No. 16 fitted the bill perfectly. And it came in a bottle larger than 33 cl. Result.

I bought some Danish cheese for

Andrew. He's so easy to buy presents for. You should see the way he looks at a supermarket cheese counter.

SmørrebrødThe girl serving in the sandwich shop was very friendly. I'd already spotted what I wanted. A schnitzel. 35 crowns, according to the price list. Except they were out of schnitzel. What I'd seen was breadcrumbed fish. Close enough, and two crowns cheaper.

As usual, it took Mike a good deal longer to decide. That's why I always go first. Not because I'm an impatient bastard. Though, come to think of it, I am an impatient bastard. I hate waiting to get served in a pub. That's why I'm always so nice to the barstaff. Mike bought two sandwiches. More proof that he eats double what I do. One he ate in the shop. The other was for the plane. As was mine.

There's an upside to having to pay for food on flights. The stuff they offer is usually pretty crap. If it's free, I feel obliged to eat it anyway. If it isn't free, bringing along your own doesn't seem so financially irresponsible. And it's bound to taste better.

Beer breakfast

Beer breakfastI had my breakfast back in the hotel. The leftovers from Saturday's supper. Washed down with

Refsvindinge. Mike looked disapprovingly at me. "Are you going to drink beer for breakfast?" I thought he knew me. Of course I was.

Ale No. 16 is only 5 point something ABV. Barely alcoholic, really. I explained how in 1839 Reid's weakest beer, IPA, was stronger. "Everyone used to drink beer in the morning." He didn't look convinced. "Winston Churchill started every day with half a bottle of champagne." He still didn't look convinced.

I couldn't really use the table beer argument to rationalise the second beer I cracked open, a

Carlsberg Elefant. Mike didn't say anything, but gave me A Look. The Elefant was left over from Friday night. I couldn't take it on the plane and I certainly wasn't going to throw it away. It was sugary, alcoholic goodness. Well, sugary, alcoholic mediocrity. But that was good enough.

We'd been saving

plan-b until our last day. We wanted time to enjoy it properly. Mike had been looking forward to it for weeks. I hoped it did really open at 12:00 on Sunday. Mike's disappointment would ruin the day if it turned out to be shut. I'd already discovered that the opening times listed in

The Copenhagen Pub Guide for two other pubs were wrong. Must mention the errors to the idiot who writes it.

Now masters of the routes, we took one of the jauntily orange-painted buses to Hovedbanegård. I repeated the pronunciation of Hovedbanegård in my head all the way there. Still not enough glottal stops in my version. The real Danish way of saying it has little else.

We dumped our luggage in a locker at the station. Then got an S-Tog to Nørreport. We'd really got the hang of Copenhagen's transport system. Just in time to go home. They could definitely do with improving the bus maps in the bus shelters, if you want my opinion. Which you probably don't.

plan-b

plan-bIt was a little after noon. Not having eaten for two hours, Mike was hungry again. "What about a sausage?" he suggested, "Isn't that a sausage wagon over there?" Right on cue, a pølser vøgn had appeared. Medister. That's the name of the one like a bratwurst. "One medister with no gunk, please. With bread." I was soon full of greasy, meaty goodness. It was to be our last sausage of the weekend.

"We need to go this way" I said confidently, dragging Mike across a busy road. I had a Google map to guide me. We strolled along a pedestrianised street. "Any of these streets will do." I sounded convincing. I was convinced.

Though the streets didn't seem to match my map. It was hard to be sure, as most of the streets on the map were unnamed. "Why don't we use my map that has the names marked." Mike said. OK smartarse, we'll use your map.

Fair enough. I had taken us in 100% the wrong direction. It's an easy enough mistake to make when you've been hypnotised by a distant pølser vøgn. That's my explanation. "You always have an excuse for everything." Dolores constantly tells me. I don't understand what she means. Explanations. That's what I give. Excuses are for when you've done something wrong.

"The next across street is Gothersgade" I was still confident, despite my slight error earlier "We need to go down here." Something didn't look quite right. Couldn't recall there being a park. Time to check the address. Frederiksborggade 48. "Sorry, we need to go back to the street we just came from." I was only one street out. Come on, it wasn't any biggie. Mike didn't say anything. No need. I could see the look in his eyes.

Seeing people sitting outside

plan-b was a great relief. It was open. Had it not been, I'd never had heard the last of it.

Inside, I was slightly disappointed to see that the deli-style display cabinet had gone. I'd quite liked its inappropriateness. And the way the owner had dived into the bottles piled in it and plucked out plums. I love the idea of a pub where even the owner isn't quite sure what's in stock.

The new counter and serving area looked more professional and actually designed for a pub. Like I said, not quite as charming. But undoubtedly far more practical. You have to temper sentiment with practicality. The rest looked unchanged. It's easy to imagine that the furnishings have been recycled, snatched from the street minutes before the binmen arrive. No two chairs are the same.

The tiny front room was filled with diners. About half a dozen people. So we went to the tiny back room, where there was a table free. The other two were occupied by beer geeks. "I know that guy. He's at every festival I go to." said Mike pointing at a bloke in a green T-shirt. At the other table someone was reading ØLentusiasteN.

We had the table next to the decks. Record decks. Very handy for checking what's being played. "I bet you like this" I said to Mike. An old soul album was playing. I was right. The owner's approach to music seems very similar to his approach to beer. Disturbingly eclectic and determinedly quirky.

"My god, they've got beer from

Chýně." I told Mike. How the hell did they get that? The brewery is in a village with about three houses. I exaggerate. There may be as many as six. If you include the brewery.

I ordered a large

Chýně 17º Polotmavé. "It's not as fresh as it was." The lanky, bearded owner very honestly told me. "Make it a small one, then." When we'd been here last - two or three years ago - Mike had been very impressed by the

Slottskällans christmas beer he'd tried. He was disappointed to learn they no longer had it. I left him in discussion with the owner. I guessed he would, as usual, not be rushing into a decision on what to drink.

Mike's long Q & A session with the owner taught him that they no longer had anything Norwegian or Swedish on the menu. He'd had to settle for something else. Can't remember what. Just that it cost 100 crowns. "I had been going to say you could buy me my first beer, but this was too expensive." I was puzzled. Why should I buy him a beer? "It's my birthday." He'd kept that one quiet.

"I bet you can't guess who the singer is." I'd just checked the label. A version of Shakin' All Over, sung by a old female voice, was coming out of the speakers. The backing was pretty shit hot. Almost as good as the original. I knew the singer, but who was the band? "You'll never guess the singer in a million years." "Connie Francis?" "No." "Nancy Sinatra" "Miles out" We continued in this vein for a while. I gave Mike a clue. "She's better known as an actress." Mike named most of the female stars from the forties and fifties. "Older than that."

This was fun. No way he was going to get it. He started on thirties film stars. "Did she make a couple of films with W.C. Fields?" Bastard. He'd guessed it. Mae West. I knew that she'd had a strange singing career towards the end of her life. Hadn't expected any of her recordings to be much cop, though. Or Mike to work it out.

The owner came by to change the record. I complimented him on his choice choice of music. He showed me the cover. The band clustured around Mae looked familiar. Then again, all those moptops look the same. "Who's the band?" I asked him. "The Standells." No wonder it sounded shit hot. I thought I owned all their recordings. Evidently not.

The new record started. Plaintive, primitive, electric guitar and a whiskey-raddled voice. Proper Capstan Full Strength blues. Howlin' Wolf. What good taste. In pubs, I prefer silence to music I dislike. The owner was welcome to keep spinning disks all day, as far as I was concerned. Great stuff so far and good drinking music.

As the afternoon passed, I began to worry if I had enough crowns to pay the bill. I was sticking with draught beer. That was just 45 crowns for 40cl. The bottles started around 60 crowns for 33cl and spiralled up to more than I had in my wallet. Some almost matched my mortgage.

I asked for a

Great Divide Barley Wine. The strongest beer on tap. My hands had been getting a bit twitchy. "You might want to try it first. Yesterday a customer told me it was their Double IPA, not the Barley Wine. Though it says Barley Wine on the keg." He poured a little into a glass. I gave it a sniff. C hops. That told me nothing. I checked the colour. In that beige area between dark amber and pale brown. Is a DIPA dark? Are American Barley Wines pale? As I couldn't decide if the beer was pale or dark, it was academic anyway. I took a sip. Bitter and alcoholic. No help there, either.

"What is the difference between a DIPA and a Barley Wine?" I asked. I wasn't being a clever pants. I really did want to know. The owner didn't seem any more able to pin down the distinction than me. "Yesterday I thought it was the DIPA, but now I'm not so sure." Hang on. Valuable drinking time was being lost. What did I care which it was? "Give me a big one."

It wasn't that bad. A bit more grapefruity than I would like. But I could put up with that for the alcohol burn. That and the malty goodness. I'm a right tart when it comes to beer. My head can easily be turned.

Mike went to the bar and came back with an unopened bottle of

Nøgne Ø Dark Horizon that the owner had fished out of the cellar. It was one of only two Norwegian beers he had. "It costs 295 crowns, but the owner said we can have a discount if we let him try it." There's an offer I've never had before. Having recently read a discussion about whether

Dark Horizon was an RIS or a Barley Wine, I suspected Mike wouldn't like it. "You won't like it." I told him. We declined the kind offer.

I'd decided what I was going to get Mike as a birthday beer. I hoped he'd like it. As I've already said, he's very picky. It was pretty expensive, 100 crowns, but not unreasonable for what it was. 2005 Hardy Ale. Should be safe with that. Aged and not American. He took a gulp. "That's really nice." Phew. Got something right at last. I knew he wasn't just being polite. Mike doesn't do just being polite.

At 15:30 it was time for us to leave. At the bar to pay, we noticed that the owner hadn't been able to resist the

Dark Horizon. "Do you want to try it?" When have I ever refused a beer? He poured us a small glass each. Powerful stuff, but pretty nice. Smooth, despite the roast and alcohol. To my surprise Mike liked it to. Maybe it being free helped. The landlord had confirmed himself as a top man in my eyes.

My fears of insufficient funds to cover the bill proved unfounded. I left with 280 crowns in my pocket. Brilliant. Maybe even enough to get pissed in the airport.

AirportThe check-in hall is right above the station in Copenhagen airport. There's convenience for you. We checked which desk we needed. Terminal 2. We were in terminal 1. Not quite so convenient. To get to Terminal 2, we had to walk through several shops, dodging between the shelves. "It's like Singapore. They're always making you walk through shops there, too." I told Mike.

Once we were checked in, I looked for somewhere to dump my crowns. I spotted a food shop. Or rather food and drink shop. A bottle of aquavit seemed a sensible choice. And a miniature of Famous Grouse for the plane. Mike came up with a packet of salmon. "Can you get this for me? I'll give you the money." (When I got home yesterday Dolores was clutching my receipt from the shop. "What's this salmon? I can't see any salmon in the fridge." "That was Mike's." I hope she doesn't always keep such a close eye on my purchases.)

I still had 180 crowns. "I'm going to have a drink" I told Mike. "I'll see you at the gate." he replied. It wasn't far. No problem. I went to a cafeteria cum bar. I got myself a tuna sandwich from the food bit. You have to maintain a balanced diet. "How much is Famous Grouse?" "28 crowns for a single, 55 for a double and 79 for a triple." "I'll have a triple then." A perfect accompaniment for my sandwich. I counted my change. 69.25. "A double Famous Grouse, please." It was an Eight Ace sort of moment.

Good job I'd had that sandwich. The whisky made me feel a bit queasy, even with a protective covering of food. I hoped Mike wasn't getting impatient at the gate. I'd taken a good 6 minutes.

We were jammed like anchovies in a barrel on the plane. Not a free space. And I had a middle seat. After 15 minutes waiting on the tarmac with inadequate air-conditioning, sweat was starting to drip from my forehead onto my book. It looked like I was finally going to finish it, after just 6 months. If I didn't wash the print off with my perspiration first. In Amsterdam, I have no time for novels. I average one every two years. Getting to the end of this one would be cause for celebration.

The padded schedule meant that, despite leaving 20 minutes late, we arrived in Amsterdam just about on time. I'd decided I was going to save money and take the train and bus back this time. No taxi. We got to Schiphol station just in time to see the Lelylaan train disappear from the board. The next one was in 15 minutes. "I'm getting a taxi. I can't be arsed to wait." No way I could wait until 20:00 for a train. I'd miss the start of Tatort.

EpilogueI don't know what it says about my normal lifestyle, but over a weekend of beer drinking, I lost 3 kilos in weight.

plan·bFrederiksborggade 48,

1360 København.

Tel: 33 36 36 56

Fax: 33 36 36 57

http://www.cafeplanb.dk/

Brewing IPA

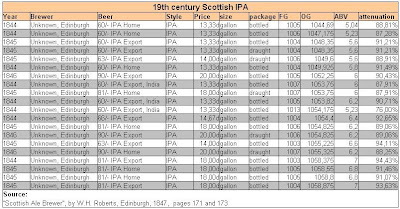

Brewing IPA If 22 pounds per quarter were being used, 6 pounds of hops were added to the first wort at the beginning of the boil. After 20 minutes, another 8 pounds were added and the boil continued for another 50 minutes. The first wort was transferred to the hop back and the second wort boiled with the remaining 8 pounds of hops for two hours. The hops from the first wort were left in the hop back and the second wort drained through them to drive out the first wort that had been soaked up by the them. (Source: "Scottish Ale Brewer", WH Roberts, Edinburgh, 1847, pages 164-165.)

If 22 pounds per quarter were being used, 6 pounds of hops were added to the first wort at the beginning of the boil. After 20 minutes, another 8 pounds were added and the boil continued for another 50 minutes. The first wort was transferred to the hop back and the second wort boiled with the remaining 8 pounds of hops for two hours. The hops from the first wort were left in the hop back and the second wort drained through them to drive out the first wort that had been soaked up by the them. (Source: "Scottish Ale Brewer", WH Roberts, Edinburgh, 1847, pages 164-165.) Cleansing took place in puncheons, which were filled up with ejected wort every two or three hours. Roberts warns of the dangers of filling up with wort that is cloudy, as it will just extend the cleansing period and create more work. Fermentation in the puncheons continued for 14 to 20 days, after which time the beer, which was already quite clear, was racked into hogsheads. When any head had subsided, a pound of hops was put into each hogshead which was then bunged down. (Source: "Scottish Ale Brewer", WH Roberts, Edinburgh, 1847, pages 167-168.)

Cleansing took place in puncheons, which were filled up with ejected wort every two or three hours. Roberts warns of the dangers of filling up with wort that is cloudy, as it will just extend the cleansing period and create more work. Fermentation in the puncheons continued for 14 to 20 days, after which time the beer, which was already quite clear, was racked into hogsheads. When any head had subsided, a pound of hops was put into each hogshead which was then bunged down. (Source: "Scottish Ale Brewer", WH Roberts, Edinburgh, 1847, pages 167-168.)